Grave Legacies: The Racialized Origins of the Zombie Myth

By Kelli Weston

All else lost to them, the enslaved Africans bore to the Americas fragments of the religions they practiced in their homelands, and combined with indigenous rituals and European folk tradition, the first decidedly American religion was born: voodoo.

The zombie film, in its original form, was inevitably a tale of race, whether the zombies themselves were Black or not. The figure had not yet been so cleanly excised from its origins in Haitian Vodou (distinct, one must add, from Hollywood’s “voodoo”) and seemed instinctively primed—if not helplessly bound—to pantomime the condition of the slaves. Its very context, culturally and cinematically, mirrors their bizarre provenance: born of the new world, compelled to do the bidding of a depraved master, and psychically rent from their own bodies.

The zombie is minstrelsy incarnate. Those early horrors would stubbornly cling to their perilous and labyrinthine Caribbean facsimiles—to the zombie as a racial bogeyman, in other words—even as their interests grew more divided. The films King of the Zombies (1941), its remake Revenge of the Zombies (1943), and Voodoo Man (1944) all clumsily wedded mad (Nazi) scientists and Black sorcery: a crude phantasm of the savage and sophisticated evils white Americans presumably faced at home and abroad. Never mind that the Nazis so admired how efficiently America had stripped its Black, Asian, and indigenous populace of rights and citizenship, that they designed the Nuremberg laws with American legislation as a model. With the turn of World War II and the dawn of the Cold War, films pivoted to the anxiety around foreign adversaries, which, from then on, proved an abiding preoccupation of the subgenre: from Creature with the Atom Brain (1955) to Invisible Invaders (1959) to Deathdream (1974) and Shock Waves (1977).

Indeed, the zombie has undergone several transformations that have by now rendered the creature ahistorical: an exemplary displacement, as much of what accounts for American popular culture finds its genesis in Black communities from whence it is eventually estranged. These deceptively cosmetic revisions, precipitated by various social and political shifts, ultimately sired an altogether new beast: from the ambling corpse, either magically or scientifically reanimated, to the rabid and infected not-quite-dead horde, mouths foaming and bodies convulsing, delirious with greed for flesh, most memorably 28 Days Later (2002) and the recent Train to Busan (2016). The last enduring vestige of the zombie—the chillingly vacant gaze, evidence of their spiritual absence—whispers its unsavory beginnings.

In 1929, William Seabrook detailed his travels through Haiti in the bestseller The Magic Island, and famously imported the zombie as we commonly know it to Americans. But cinema had long betrayed a curious fascination with voodoo or, more precisely, hysterical conceptions of it. Early films Voodoo Fires (1913), Unconquered (1917), and The Witching Eyes (1929) forecast the arrival of Victor Halperin’s White Zombie (1932), the first feature-length zombie film. The descriptions of zombies authored by Americans (including Seabrook)—and later portrayed on screen—frequently paralleled racist language wielded against Black communities: they possess limited intelligence; they do not feel pain the way the living/Europeans did (a myth that persists in medical circles and yields devastating consequences for Black patients). Of his initial encounter with the zombie, Seabrook writes, “They were in truth like the eyes of a dead man… It was vacant, as if there was nothing behind it.” In part, the zombie functions so well as a racialized bogeyman because usually they preserve little, if any claim, on human compassion. Unlike their dead, equally hybrid kin—the ghost, the vampire—the zombie’s particular transmutation severs them from personhood, characterized by their lifeless gaze. They are automatons and thus summarily vanquished, with or without remorse from our heroes.

It is unsurprising, then, given these murky beginnings in racial animus and colonial paranoia, that the earliest zombie films locate their horror in white women’s constantly imperiled sexuality. According to the scholar Lizabeth Paravisini-Gebert, certain patterns unite various accounts of the zombified woman—as reported by Seabrook, Zora Neale Hurston, Harry Franck, among others—which suggests they originate from one basic template: “...the coveting of a beautiful, light-skinned or white upper-class girl by an older, dark-skinned man who is of lower class and is adept at sorcery; the intimations of necromantic sexuality with a girl who has lost her volition; the wedding night…as the preferred setting for the administration of the zombie poison…” Predictably, filmmakers would recycle these core elements, which conveniently echoed a long familiar mythos.

White Zombie (above) was directly inspired by Seabrook’s accounts and most transparently reproduces his pernicious framework. Fresh from his star turn as Dracula in the 1931 film adaptation, Bela Lugosi plays zombie master “Murder” Legendre, enlisted by plantation owner Charles Beaumont (Robert W. Frazer) to secure the affections of Madeleine Short (Madge Bellamy), already happily engaged to unsuspecting banker Neil Parker (John Harron). They are all white outsiders to Haiti, but Legendre, most of all, bears a peculiar liminality. He may or may not be coded here as Creole, but nevertheless he operates as a perverse emblem of miscegenation. He owes his wealth to the (white) zombie servants who restlessly toil away in his mills, but his “Black” practices (voodoo), for which he is known, exclude him from the white middle class on the island. Feared by Haiti’s European elite and Black population alike, he straddles both societies while belonging to neither.

Madeleine, on the other hand, classically embodies racial and feminine purity: an innocent whose chastity is at risk. Legendre emerges in the impotent Beaumount’s stead, a white man, no less, wielding a Black phallus: voodoo. Considering what we know the zombie represents—the slave—Legendre already traps Madeleine in a not purely “white” state. Upon learning of his beloved’s plight, Neil cries out, “Not alive…in the hands of natives…better dead than that!”

White Zombie is not, apart from its historic import, an especially memorable or well-acted film, but the film nevertheless spawned a generation of zombie cinema. Perhaps the least successful—and, arguably, the most provocative—of these was George Terwilliger’s Ouanga (1936), a little-known horror about a biracial voodoo priestess Clelie (Fredi Washington), set on revenge after her former lover, a white man, decides to marry a white woman, whom Clelie intends to zombify. Washington—then known for her performance as Peola Johnson, the quintessential cinematic Tragic Mulatto in Imitation of Life (1934)—plays a similar role here, in a strikingly different tone: all feverish rage (rather than feverish shame) over what the racial hierarchy has denied her. For in every other sense, she lives as a white man. Like Legendre, she is a wealthy plantation owner, and furthermore, independent, glamorous, and sexually autonomous. But just as he exemplifies, all at once, the alienating and deathly status miscegenation incurs, so, too, does Clelie, using voodoo to penetrate a white woman, to effectively “turn” her Black.

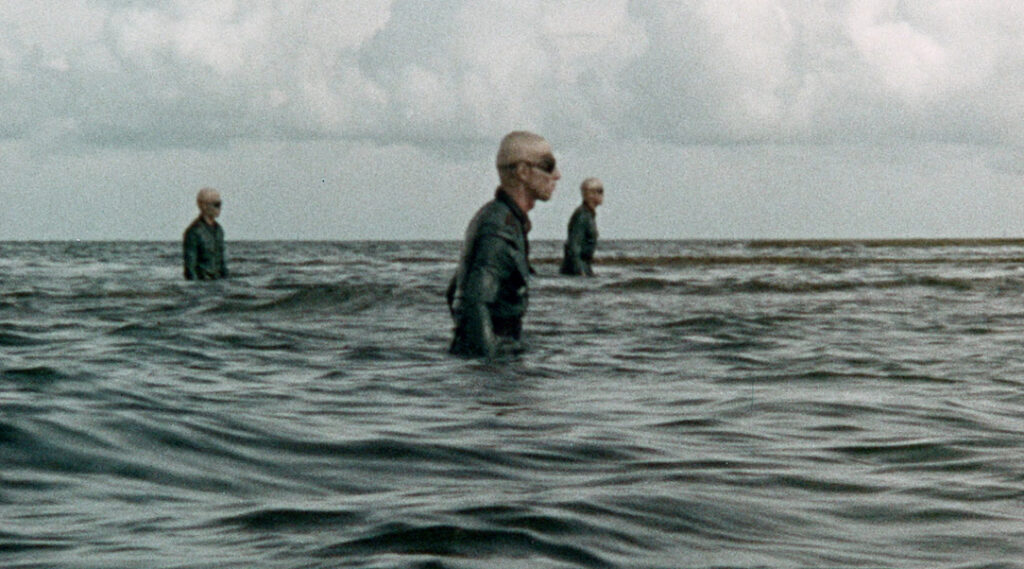

The most sophisticated of these early ventures is I Walked with a Zombie (1943), one of the many extolled collaborations between director Jacques Tourneur and legendary producer Val Lewton. Yet again, a white woman’s zombie (racialized) state is linked to sexual transgression and comes to embody the “tragedy” of miscegenation. A naive young nurse, Betsy (Frances Dee), travels to the fictional island Saint Sebastian, where a sugar plantation owner Paul Holland (B-movie horror fixture Tom Conway) has tasked her to care for his catatonic wife, Jessica (Christine Gordon), who’s afflicted with a mysterious walking illness. A smitten Betsy commits herself to restoring Jessica, whose sunken gaze reveals her as a zombie. But unlike White Zombie and Ouanga before it, a white woman is responsible for Jessica’s state. Mrs. Rand—mother to Paul and his half-brother Wesley—confesses that after she discovered Jessica and Wesley were having an affair, she asked the houngan (male priest in Haitian Vodou) to turn her daughter-in-law into a zombie. So, Jessica’s zombification can be traced back to a familiar sexual order: together the Black male houngan and the white upper-class Mrs. Rand conspired to produce Jessica, the walking symbol of interracial reproduction, an “unnatural” locus of horror.

George Marshall’s The Ghost Breakers (1940) and Zombies of Mora Tau (1957), directed by Edward L. Cahn—who also directed zombie thrillers Invisible Invaders and Creature with the Atom Brain—shy away from blood mixing to reckon more broadly with the zombie as the ever-lurking revenant of slavery. Even Ghost Breakers, with its retrograde Black characters, ultimately hinges upon this grave legacy. The heroine expects to inherit a plantation in Cuba, rumored to be haunted by ghosts and zombies. The Black men here are either buffoons or catatonic, but all these films in one way or another harbor the same great fear—less crudely expressed—about proximity to Blackness, always threatening to penetrate white society. Now the zombie may richly signal any number of social failings (war, plague, the bureaucratic approach to the “disposable” masses), but the figure cannot escape its racialized birth. Somehow the migration away from these original anxieties announce a still lingering, merely unnamed haunting, a past too unspeakable to ever confront.

Pictured at top: I Walked with a Zombie (1943)