Icons: Framing Images of Black Women on Movie Posters

By Racquel Gates, Associate Professor of Film, Columbia University

Introduction

Black women occupy a fraught position within American cinema: their iconic performances form the backbone of so many memorable films, yet the film industry’s ongoing racism often relegates them to stereotypical roles and simplistic tropes. Despite this, Black women have imbued their roles and cinematic history itself with creative ingenuity, bringing out the best of paltry material and elevating simplistic character types with nuance and originality.

This essay reflects on Black female iconicity as a concept and its implications for our understanding of film and film history. If we take up scholar Nicole Fleetwood’s theory that racial icons illustrate both venerability and denigration and tell us something about attitudes toward race in society more broadly, the promotional material considered here illustrate a range of depictions, attitudes, and assumed audiences.

The posters that illustrate this essay (which were on view at Museum of the Moving Image from April 2021 to June 2022) were selected to highlight Black women’s centrality in the story of American filmmaking, and serve as correctives to the oft-told story that Black actors and actresses are not marketable on their own. This incorrect “logic” is often presented and taken as fact, and has long been used to justify the industry’s lack of support for Black-led, Black-cast, or Black-directed films. As scholar Monica Ndounou argues, even Black films that are box-office successes are still interpreted as “failures” unless they outperform in every normal measure of success. Yet if “Black films don’t sell,” then how do we account for the film industry’s continued reliance on Black films as guaranteed sources of box office revenue, especially in times of economic turmoil, as evidenced by the boom of Black film production in the 1970s and the 1990s? These posters challenge that myth, demonstrating that the film industry knows quite well the power of Black star power, Black stories, and Black audiences, in spite of its proclamations to the contrary.

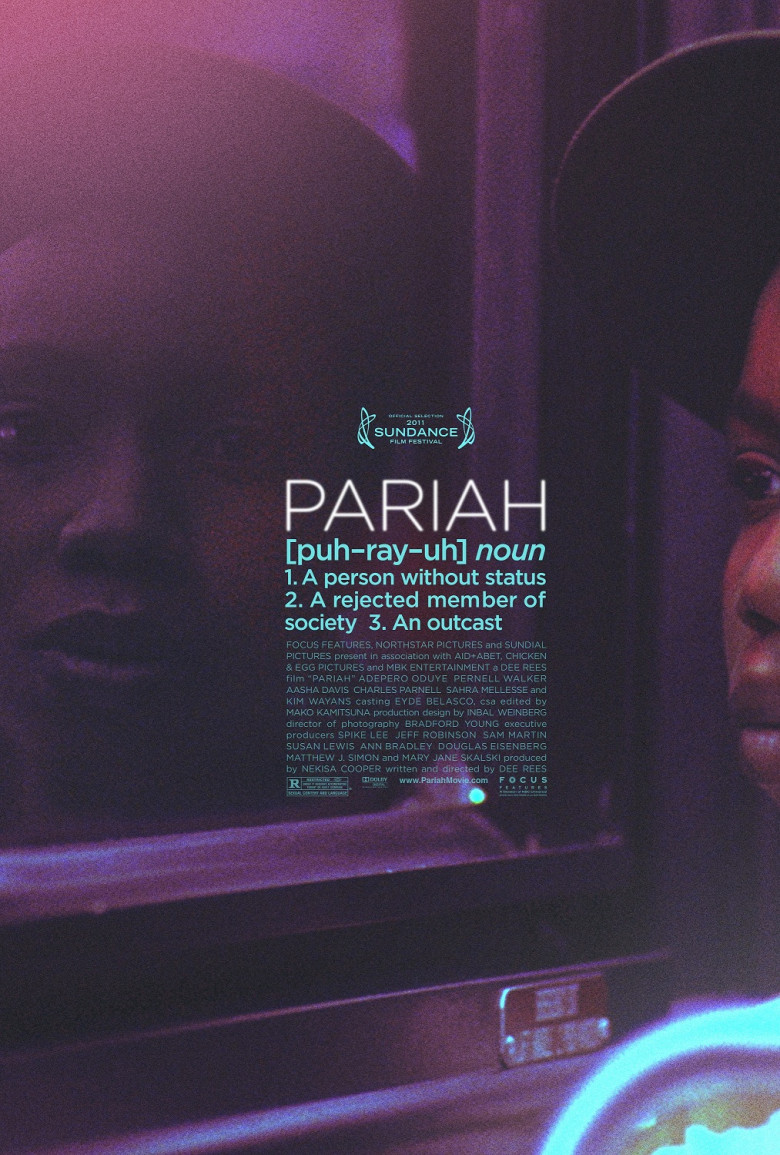

Beyond the matter of box-office marketability, these posters also invite us to reconsider the presumed audiences for these films. From “race films” to independent features to Hollywood blockbusters, each suggests a different audience and a different relationship between audience and icon. Black audiences in the 1930s would likely have welcomed the opportunity to see Louise Beavers in the context of a “race movie,” shown in theaters serving Black moviegoers, a quite different experience from seeing her play domestics in white worlds in segregated theaters. We might imagine the joy of discovery in seeing underrepresented identities in the more contemporary independent films The Watermelon Woman (1996) and Pariah (2011) (the latter’s poster chosen with input from fans). While posters are only one element of the story of the relationship between images and audiences, their function as material culture designed to entice audiences reminds us that films are dynamic texts predicated on an active and ongoing relationship between creator, object, and viewer.

The representation of Black women on movie posters demonstrates the complicated place Black stars hold in cinema. In some ways, they align neatly with discourse around white stars; in others, they sharply depart. Early in her career, Nina Mae McKinney was referred to as “The Black Garbo,” demonstrating how white stars, and whiteness itself, functioned—and continues to function—as the unquestioned default against which Black actresses were, and are, measured. Likewise, the public personas for Dorothy Dandridge and Lena Horne, other stars of the classical Hollywood era, were similarly constructed within the molds shaped around white starlets. As might be expected, these talented actresses struggled within such ill-fitting models of stardom, hampered by raced and gendered standards that did not apply to their white counterparts, laboring to find roles that were creatively fulfilling and did not run afoul of the film industry’s censorship codes or other forms of codified marginalization. Horne complained that she was most often featured in standalone musical numbers outside of the main narrative of the white films in which she appeared, only receiving the opportunity to do any real acting when MGM decided to make a rare Black cast film like Cabin in the Sky (1943) or when they loaned her out to a different studio, as with Stormy Weather (1943).

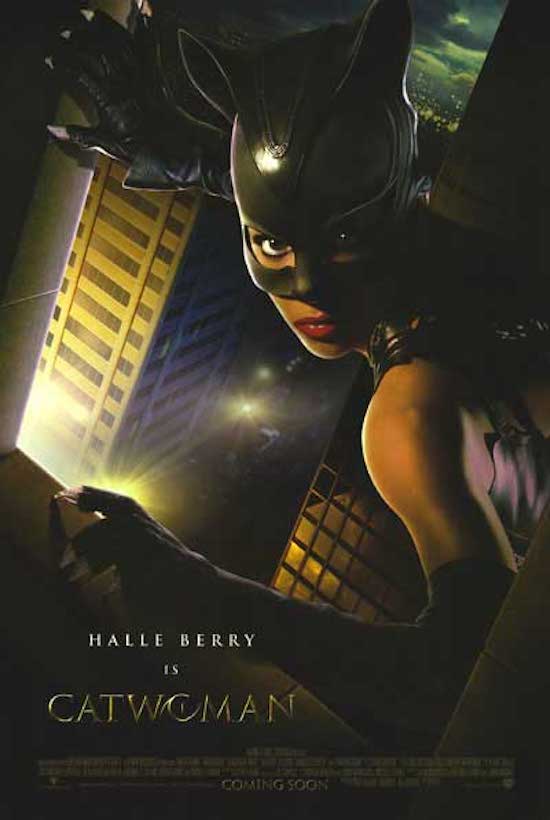

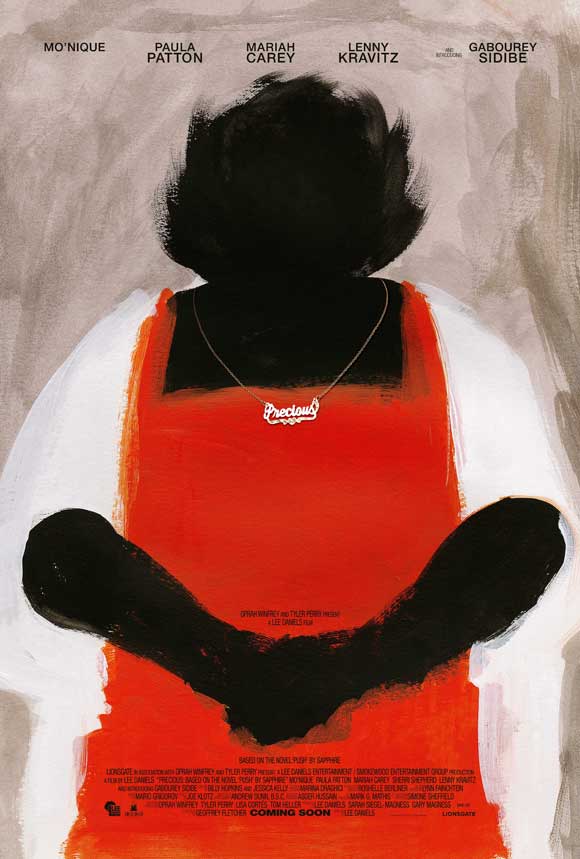

Horne’s struggle to find her place in an industry not designed for her is just one example of the myriad challenges that Black women in film have faced. Even with a demonstrated record of box-office and critical success, Black actresses even today do not typically enjoy the same career boosts as white actresses after they have a hit film or win a prestigious award. Academy Award–winner Halle Berry—the first Black woman to win a Best Actress Oscar (Dorothy Dandridge was the first to be nominated in that category 47 years prior)—publicly lamented the fact that her historic win did not open doors for other Black actresses. Fellow Academy Award–winner Mo’Nique (Best Supporting Actress for 2009’s Precious) candidly expressed her disappointment that the award only seemed to engender negative feelings about her in the industry and a reputation for being “difficult,” itself a notion disproportionately applied to Black women in film and beyond.

There is much work to be done to fully recognize the contributions of Black women to the film industry; taking seriously the art of these movie posters is vital in understanding the significance of Black women’s images and performances. Not just marketing tools, these posters are objects that capture the essence of a film’s message while also elucidating larger ideas about Black women in both cinema and society.

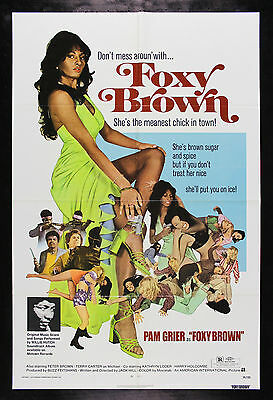

For every poster that was selected for inclusion in this essay and the exhibit at MoMI, there were several others that could have been showcased in its place. The range of Black women stars, and the fascination the public holds for them, is far wider than a single exhibit can capture, and this selection is representative in the truest sense of the term. In some of these posters, the star—such as Halle Berry or Whoopi Goldberg—is the main draw, signaling immense box-office popularity at the height of her career. In others, a genre or specific film movement known for showcasing Black women takes center stage, such as the blaxploitation genre, of which Pam Grier’s Foxy Brown stands as representative in this exhibit; other films of this genre that might as well have been featured here include Cleopatra Jones (1973), Sugar Hill (1974), and Grier’s canon of work including Coffy (1973) and Sheba Baby (1975).

In what follows, I offer thoughts on the significance of each of the posters and lobby cards selected for this exhibit, gesturing toward both the specific and broader meanings that these materials capture.

Life Goes On (1938)

Louise Beavers is the clear star of Life Goes On, directed by William Nolte in 1938. This film, as well as Straight to Heaven (discussed below), are known as “race movies”—films with Black casts that were marketed toward Black audiences in the 1930s and 1940s. Though others are depicted alongside her on these lobby cards, Beavers is front and center. Some critics have dismissed her because she frequently played “mammy” types, but this perspective overlooks Beavers’s immense star power—which is why she is centered and named in the film’s promotional material—as well as the uniqueness of her performances, even in roles that were, on paper, one-note stereotypes. The tendency to overlook Beavers’s significance says much more about our own anxiety around Hollywood stereotypes than about the actresses who played them, with the unfortunate effect of blaming an actress like Beavers—who made the absolute most of every part that she was given—rather than directing our attention at the broader Hollywood system itself and its politics of representation.

Straight to Heaven (1939)

Like that of Louise Beavers in Life Goes On, Nina Mae McKinney’s stardom is on display in the lobby cards for Straight to Heaven. Though she actually plays a supporting role in the film and Jackie Ward plays the main character, McKinney’s celebrity is clearly understood as the film’s draw: hers is the only name that appears along with the title in the film’s promotional material. Even contemporary viewers recognize her “It factor” quality on-screen, with online reviewers highlighting her performance as the standout aspect. With charm, sex appeal, and a hint of edge, McKinney was not only a star in the United States or in American “race movies” but was also a global success, appearing in productions all over the world. One explanation for the casting of a then-unknown Lena Horne in The Duke Is Tops (1938) is that McKinney, the director’s first choice, was in Australia working on a project. Europeans nicknamed McKinney “The Black Garbo” to articulate the exquisite beauty of her face, a description that frames McKinney as a derivative version of a white star and, moreover, falls woefully short of capturing her incredible magnetism.

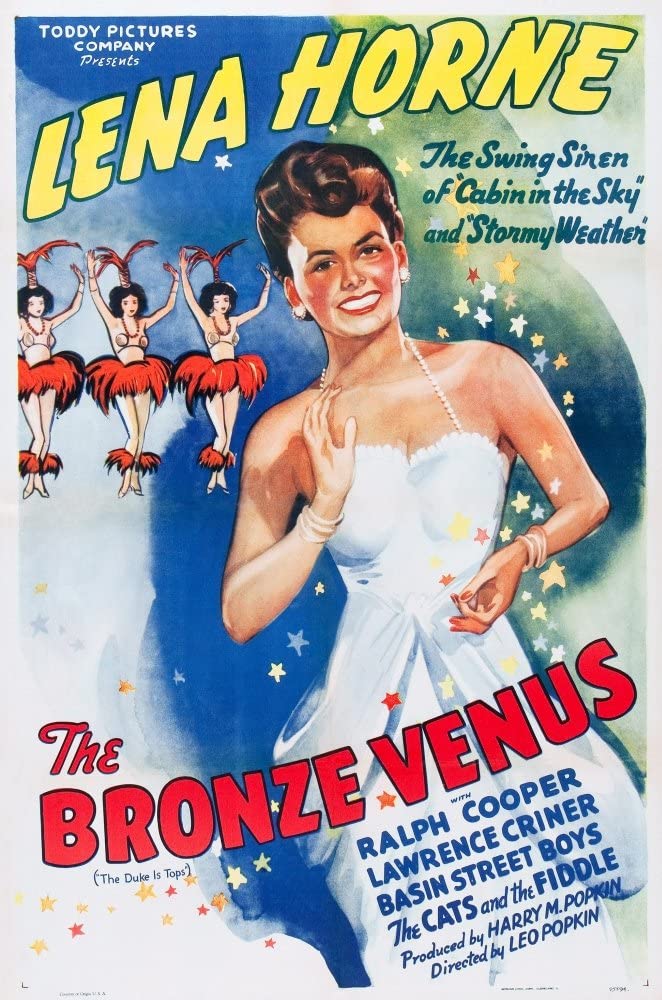

The Bronze Venus (1943)

In 1938, Lena Horne appeared in The Duke Is Tops, a “race movie” about a theater promoter who falls in love with a singer. Ralph Cooper starred in, wrote, and co-directed the film with listed director William Nolte (who also directed Louise Beavers in Life Goes On). At the time of the film’s release, Horne was not the box-office attraction that she would eventually become. But by 1943, Horne had signed a groundbreaking contract with MGM, and won acclaim for her performances in Cabin in the Sky (1943) and Stormy Weather (1943), putting her in the rare category of Black performers under contract with a major studio. To capitalize on Horne’s fame, the film was rereleased under the new title The Bronze Venus, a vivid indication of her star appeal. This is evident in her oversized image on the poster and the complete erasure of Ralph Cooper from this version, whereas the original poster for The Duke Is Tops featured the pair in a romantic embrace.

Carmen Jones (1954)

Perhaps more than any other actress featured in this collection, Dorothy Dandridge has become synonymous with her most famous role: a factory worker who seduces and casts away a naïve soldier in Otto Preminger’s Carmen Jones. Depicted as a sexy and independent temptress on the poster, standing defiantly with an oversized bed frame behind her, Dandridge’s Carmen was both an adaptation of the character from Georges Bizet’s opera Carmen, a wartime symbol of female independence, and a figure imbued with explicit and implicit ideas about Black women’s sexuality. Groundbreaking for the time, it was a Black cast film with a hefty budget treated similarly to white cast prestige films. Carmen Jones—and Dandridge’s experience filming it—is a metaphor for Black women’s struggles in Hollywood. Dandridge, who became the first Black woman nominated for a Best Actress Academy Award for Carmen Jones, fought to secure roles in a segregated Hollywood that rarely created nuanced and rich parts for Black women characters. If Black cast movies were most often comedies or musicals, and interracial romances were forbidden by the Production Code, then what place was there for a leading lady such as Dandridge? Moreover, the scandals that accompanied her love life, including her relationship with Preminger and a very public lawsuit, in which she sued gossip magazine Confidential for libel (they alleged that she had a public sexual encounter with a white stranger), demonstrate the difficult position for a Black woman who is hypervisible in the public eye.

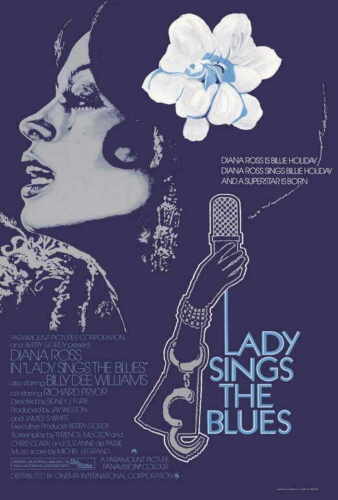

Lady Sings the Blues (1972)

The lovely image of Diana Ross on the poster for Lady Sings the Blues captures the iconic quality of the singer-actress as well as the real-life character she’s playing, singer Billie Holiday. Ross’s face and Holiday’s iconic gardenia tell us all we need to know. This dynamic—an icon portraying an icon—lends a meta quality to the film perfectly captured by the poster. Beyond the image itself, the film stands as an important moment in film history, when Motown Records developed Motown Productions in an attempt to enter the world of film. Ross’s celebrity would be the engine powering this shift, in this and the subsequent Motown Production films Mahogany (1975) and The Wiz (1978). Notably, Ross’s performance in Lady would win her an Academy Award nomination for Best Actress, alongside Cicely Tyson’s nomination for Sounder, marking the first time that two Black women were nominated in the same category.

Foxy Brown (1974)

Similar to Dorothy Dandridge and Carmen Jones, Pam Grier’s celebrity image is often conflated with her most iconic role, the Blaxploitation-era Foxy Brown. The story of a woman who goes undercover as a prostitute to exact revenge on the white drug dealers who arranged her boyfriend’s murder, Foxy Brown has often been criticized for its hypersexualized framing of Grier’s body. In the poster, for instance, the breezy dress that she wears accentuates her curves, which is repeated in the opening frames of the film’s credits, where we see Grier’s body in silhouette. And while this charge of hypersexualization is certainly true, that is not the extent of Grier’s appeal in Foxy Brown. Rather, what we get is a layered character who is at times object and agent, strong (note her gaze at the viewer in the poster) yet vulnerable, and always magnetic on the screen. In many ways, Grier’s Foxy Brown anticipates the Black woman action heroes of more recent films like Black Panther (2018).

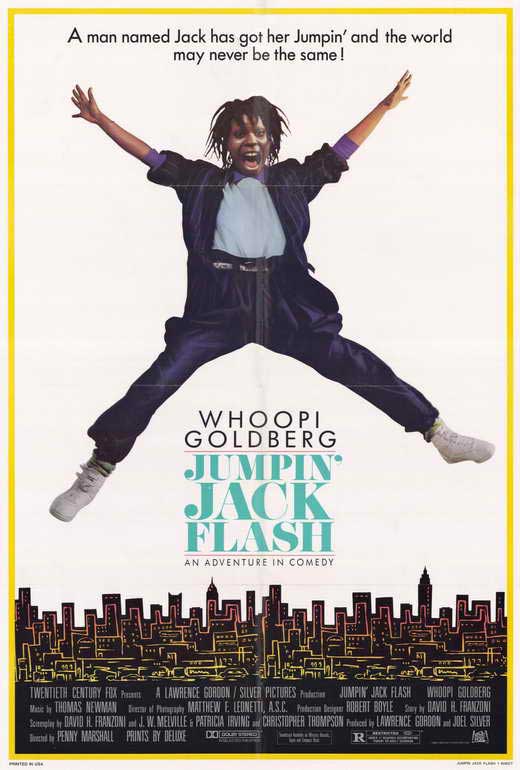

Jumpin’ Jack Flash (1986)

One of the biggest stars of the 1980s and 1990s, Whoopi Goldberg had a series of leading roles, and Jumpin’ Jack Flash was perhaps the most noteworthy. The film was representative of the unique place that Goldberg occupied in Hollywood. Existing outside of the aesthetic conventions of Hollywood leading ladies, Goldberg was a shapeshifter, taking on roles not originally written for her (Jumpin’ Jack Flash was originally intended as a vehicle for white actress Shelley Long) and imbuing them with her unique charm, wit, and persona. In the poster, Goldberg is dressed in androgynous clothing and in the midst of physical action (a cheeky reference to the title), a very different presentation of Black womanhood than in the more obviously sexualized posters for Foxy Brown or Carmen Jones. For many Black actresses who find success in crossover films, parts are rarely written with them in mind, thus placing them in a bind to make the roles theirs. Goldberg’s ability to succeed both in spite of and because of this problematic practice is evident in the immense range of films and roles that mark her long career.

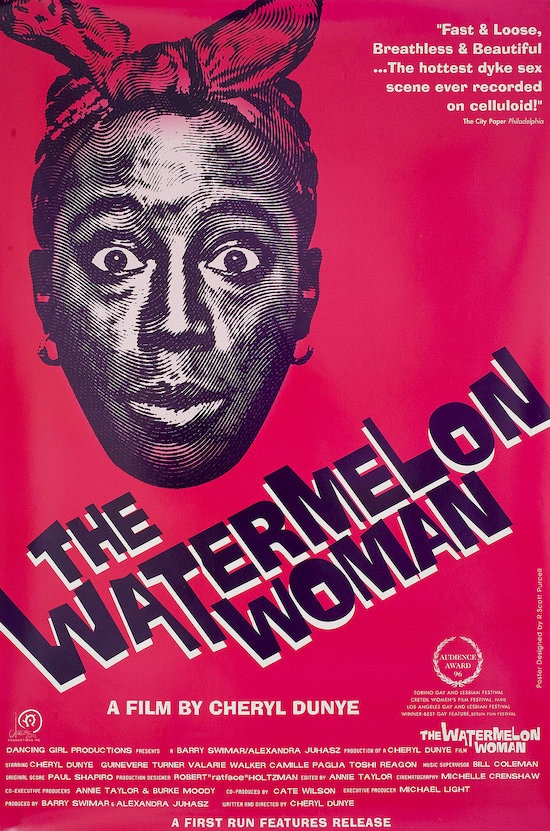

The Watermelon Woman (1996)

The Watermelon Woman is a romantic comedy-drama about a budding filmmaker’s search for information about an unknown Black actress from the 1930s, and how this research project begins to intersect with her personal life and her relationships with her friends and a new lover. The poster shows director and lead actress Cheryl Dunye wearing a kerchief, a symbol most readily associated with “mammy” figures in Hollywood cinema. The poster riffs on this association, forecasting the film’s focus: a meta commentary about revisiting Black representation of the past and seeing beyond the limiting tropes to acknowledge the brilliant performers laboring to infuse the roles with nuance and depth. This topic is just as relevant now as it was in 1996, given society’s continued reluctance to revisit some of the more thorny and problematic representations from the 1930s and 1940s. Moreover, the film’s presentation of a queer Black woman as its lead illustrates the diversity of Black communities, something often lost in mainstream depictions of Black women. Dunye’s own career in the industry working across movies and television, in independent as well as Hollywood film, is a testament to the dexterity of Black women creatives in an industry that does not afford them the same privileges as their white male counterparts.

Catwoman (2004)

Perhaps more than any of the other women featured in this collection, Halle Berry illustrates the extent to which it is understood that Black women’s images and star power are capable of selling a film—even if it’s not always acknowledged. The first Black woman to win a Best Actress Oscar, in 2002 for Monster’s Ball, Berry was not just the biggest Black woman star when Catwoman was released in 2004, she was arguably the biggest female star period. The poster, which features Berry-as-Catwoman dominating the night sky against a stunning cityscape, is perhaps a metaphor for Berry’s dominance in the film industry in the prime of her career. Though Berry has noted that her Oscar win did not create the types of opportunities that she had hoped for (and that seem to come more readily to white women Oscar winners), this early 2000s period still stands as a testament to her status as a groundbreaking icon. As the titular character in Catwoman, a big-budget comic book film, Berry’s casting demonstrated the studio’s conviction in her ability to headline a major film, an important response to the tacitly accepted view that Black stars must be paired with white ones in a film’s marketing and story.

Precious (2009)

When we think of movie posters, and especially imagery of women on movie posters, sexually objectified women’s bodies may often come to mind. Yet in Precious, the distance of the protagonist’s body type and skin tone from society’s norms is a key aspect of the story. Various posters for the film adopt different representational styles and color schemes, yet they all depict Precious (Gabourey Sidibe) by herself, with no other characters or even images, highlighting the character’s isolation but also her central role in the narrative. In the poster selected for this exhibition, the style looks like an abstract painting: Precious’s form is composed of rough brush strokes, her face blank. In many ways, this image stands in for how Black women are often treated within Hollywood: abstractions sketched on paper with little nuance or specificity. It is only the brilliance and the care of the Black women who inhabit these abstractions that makes them fully realized characters.

Pariah (2011)

Dee Rees’s independent breakthrough Pariah is a semi-autobiographical coming-of-age film about a Black lesbian teenager in Brooklyn. The stunning poster, which features lead actress Adepero Oduye bathed in lush jewel tones while gazing at herself in the reflection of a bus window, gestures toward the duality that forms a key theme of the film. The poster is the result of crowd-sourced decision-making: wanting to open a dialogue with the prospective audience for the film, the filmmakers and distributor, Focus Features, sought feedback online for the final poster selection. On the one hand, this story indicates the investment that audiences have in stories and characters outside of a conventional Hollywood formula. On the other, the very idea that Focus Features was tentative about the best way to advertise Pariah is just one example of the obstacles that films featuring non gender-conforming Black women still face.

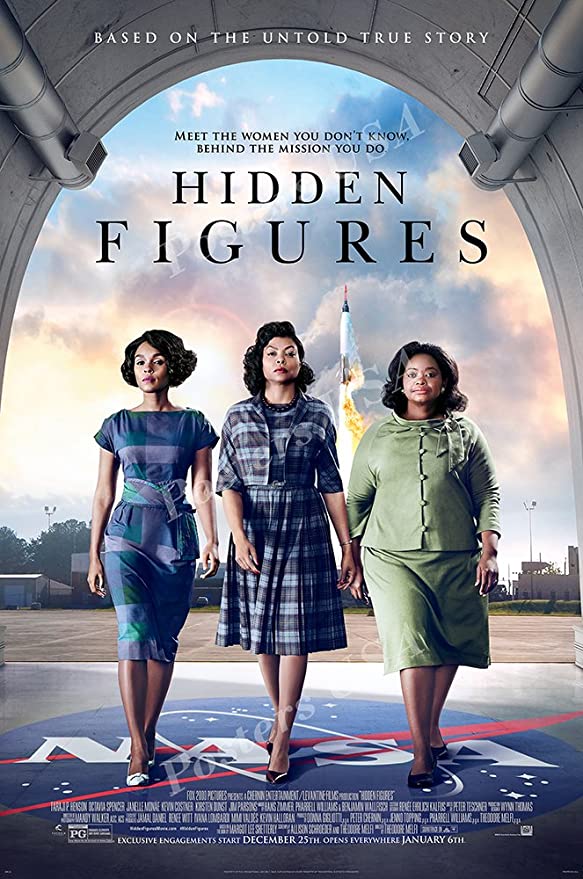

Hidden Figures (2016)

If any poster exemplifies the phrase “representation matters”, it’s the one for Hidden Figures. The true story of Black women mathematicians working at NASA in the crucial early years of the space program, Hidden Figures is a film whose significance extends beyond the screen. The poster sets actresses Taraji P. Henson, Octavia Spencer, and Janelle Monáe against the backdrop of a rocket launch. They stand together, and yet together they stand apart from the rest of NASA, a fitting metaphor for the experiences of the women that they portray. Hidden Figures rests firmly in the genre of historical film, one of the few genres in which a predominantly Black cast is not seen as an impediment to box-office appeal, a perception rooted in Hollywood’s racism, not in fact. Yet, beyond this, the framing of its three strong leads places Black women front and center, correcting their historic marginalization both in Hollywood and in history.

Learn more about MoMI's exhibition Icons: Framing Images of Black Women in Movie Posters.