Dialogues with the Unseen

An Introduction

By Juliette Yu-Ming Lizeray

This essay is published in conjunction with Dialogues with the Unseen, currently on view at Museum of the Moving Image.

As I grew up in Singapore and lived in different parts of Southeast Asia, the unseen has been a part of my everyday for as long as the seen has. In the geographies I am most familiar with, ghost stories abound, and many religions and cultural traditions engage with the spirit world in one form or another. I’ve found every country, place, and community has its own richly populated and culturally specific set of invisible realms encompassing the spirits of beings or things, deities, or energies.

What has always struck me, and what drove me to study cultural anthropology, was the importance of interconnectedness in local belief systems. The interrelation between the living and non-living is a recurring thread. Death, for example, is not always viewed as the end of a relationship; it can just as easily mark the beginning of new forms of interaction and attachment. The interconnection of the human and the non-human is also of great significance: animals and natural elements such as mountains, rivers, rocks, seas, and jungles may be seen to possess energetic potencies that need to be taken into account when we come into their presence.

Both relational dimensions—living/non-living and human/non-human—suggest a broad understanding of different life-worlds and the web of relationships of which we are a part. They are counterpoints to conceptions of the world that rely on reason alone, or those that place humans above all other life forms.

The program Dialogues with the Unseen, which features films by artists from Indonesia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam, was born out of a desire to re-envision how we relate to the world at large. By evoking the interconnectedness of things, the works on view reach beyond the self and connect with the unseen, unknowable Other with empathy and imagination.

The Return: The Imagined Unseen

For Thai artist Tulapop Saenjaroen, making The Return was driven by his desire to process the untimely death of his father, who passed away when the artist was five. When Saenjaroen made The Return in 2008, he intended for it to be at once speculative and autobiographical. In the film, Saenjaroen is seen recording a voiceover, performing his father visiting him after many years. Reflecting on his past, the artist told me he realized how much he has filled the void left by his father’s absence with invented memories.

Saenjaroen describes how, over time, his recollections of his father have become increasingly faulty and interspersed with his own projections, to the point that the line between what is “real” and what is “fiction” is blurred. Both invented and lived memories of treasured moments spent with his father coexist and constitute Saenjaroen’s perception of his childhood and identity. Instead of fighting the fictional, the artist embraces its potential for catharsis and introspection. In the final shot, his performance is revealed. Seen from the back, in a dimly lit room, he removes his headphones and leaves the frame. He would only record the voiceover once. In his words, “It would have been too painful to embody his perspective again.”

Excerpt below from The Return by Tulapop Saenjaroen, courtesy of the artist.

Cartographer Mapping Scarscapes #1: The Existential Unseen

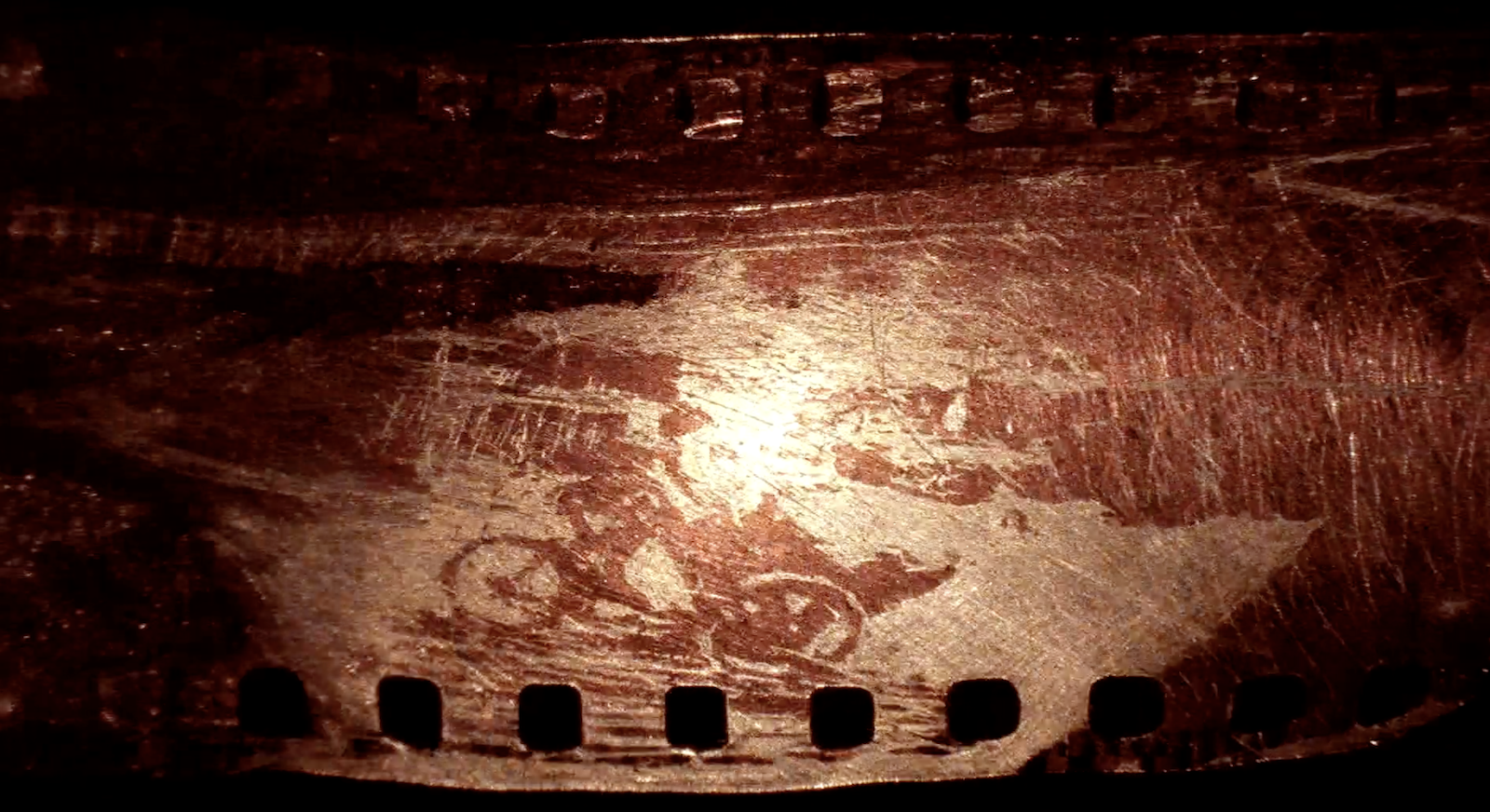

An invitation for viewers to ponder one’s journey through life, Cartographer Mapping Scarscapes #1 is a direct animation by Singaporean artist Toh Hun Ping made entirely with photo negatives. It is imbued with an existentialist quality that underscores much of the artist’s body of work.

In the years preceding the making of this film, Toh’s life had been turned upside down. He had just overcome tremendous personal upheavals and was coping with mental health issues that compelled him to turn to art and abandon a secure future as a civil servant. Cartographer Mapping Scarscapes #1 reflects Toh’s enduring quest to find the meaning of existence. Fleeting images representing both lost and projected memories evoke ideas of transience and ephemerality, and the constant motion and impressionistic, almost subliminal quality of the images reflect Toh’s own fluid and ever-shifting notion of the self.

Seen in the context of Singapore, where the artist lives, the transience apparent in the film takes on a deeper meaning. In a place where the old is swiftly replaced with the new, change can feel like the only constant. Nostalgia amidst the push for progress, the desire to preserve and the impetus to renew: these are ever-present dualities which often emerge in Singapore’s artistic expression. Yet what makes Toh’s work stand out is its lack of sentimentality or nostalgia. Instead, he stares straight into the void of dislocation with a degree of detachment that mirrors his own philosophical outlook on human existence. Referring to the flame revealed at the end, he told me that light is the “singular unchanging element of the film, whether you interpret it as a universal consciousness or God or a supreme being that gives existence to things, is up to you.”

Excerpt below from Cartographer Mapping Scarscapes #1 by Toh Hun Ping, courtesy of the artist.

The Visible World: Beyond Visuality

In Filipino artist Cristian Tablazon’s The Visible World, images seem reluctant to reveal themselves fully. They’re shrouded in blurry mystery, abstracted through hyperpixellation. Meanwhile, we hear an earnestly passionate soliloquy in voiceover, intonated by an unfeeling robot. The lyrical musings appear as a singular testimony, but are spliced together from love letters to the artist, correspondence between his parents, excerpts from his great grandfather’s 1936 komedya (play in verse) titled “Prinsipe Baldovino,” and remixed quotes from Roland Barthes.

By entwining disparate elements in an enigmatic montage, The Visible World draws unexpected connections between visual and aural layers. Gaps and images manipulated in non-realist ways produce a textured abstraction that hints at the in-between-ness of the image. The film alludes to the invisible dimensions of reality that exist beyond sight and logic.

Drawn to what he calls “visual detritus”—remnants of archives, forgotten histories left by the wayside, debris of material culture—the artist scours his own image banks for footage. As he recontextualizes his archives, Tablazon contemplates his great grandfather’s place in Philippine cultural memory and historiography.

Komedyas, descended from the Spanish comedia (play) of the 16th century, were a popular form of entertainment through the early 20th century. Tablazon’s great grandfather was one of the few artists to stage his komedyas in the rural communities in the Southern islands of the Philippines. Yet, even as his work became a part of the public archive, it often went unattributed. The Visible World is as much a meditation on what lies in the shadows, as it is a loving commemoration of family and cultural legacy.

Excerpt below from The Visible World by Cristian Tablazon, courtesy of the artist.

A child dies, a child plays, a woman is born, a woman dies, a bird arrives, a bird flies off: Decentering the Human

Filipino artist Shireen Seno’s film invites viewers to consider connections that transcend species, specifically the analogous experiences of birds and humans. Animism is a way of relating to the world in which humans acknowledge we are not the only beings with souls or vital life forces. Animals, even things, can be seen as sharing the same interior quality as humans, granting them agency and intention.

Seno points out the parallels between birds’ migratory habits and the Filipino diaspora. Her own family history is inextricably linked to transnational migration. Born to Filipino parents working in Japan, Seno spent most of her youth in Tokyo. In 2001, her father moved to Los Angeles, in the hopes of realizing “the American Dream.” Seno then spent several years in Canada before settling in the Philippines in 2009. In a recent conversation, Seno shared that growing up she felt an “emptiness of not knowing where I was from, of having to represent a country I had no idea about.” Today, she has built a home and community in Quezon City, yet her fascination with migration and its effects on belonging and identity remain.

Seno observes the world with deep curiosity and a sense of wonder. Her equanimity toward both the human and nonhuman is especially perceptible in this work. When she began her observation of birds in the Candaba Wetlands, north of Manila, she had no fixed idea or goal of what to encounter or film, other than observe the feathered creatures in their habitat. This openness flowed into the footage she ended up capturing and the way in which she edited the film. She directs her gaze, recorded through a spotting scope, first to the birds, then to her own child and partner at home. The juxtaposition of birds and humans going about their daily lives, each in their own environments, gently prods viewers to rethink our perceptions of difference and familiarity in relation to other beings.

Excerpt below from A child dies, a child plays, a woman is born, a woman dies, a bird arrives, a bird flies off by Shireen Seno, courtesy of the artist.

Xiào 孝: Unseen Forces

In Indonesian artist Cahyo Prayogo’s Xiào 孝, we see a man performing rites associated with ancestor worship, a practice linked to Buddhist, Taoist and Confucian beliefs. He prays in front of the ancestral altar in his home. We see offerings, typically the favorite food of the departed, carefully laid out on a table. He also burns joss paper, also known as paper money, for his forebears to use in the afterlife. Central to ancestor worship is the belief that the souls of the deceased continue to inhabit the natural world and have the power to impact the fate of the living. Performing these rites is both an act of filial piety (xiào 孝) to keep ancestral spirits happy, and a means to achieve blessings and good fortune.

Bo Hek lives in the kampung (village) of Tambak Bayan, one of the oldest Chinese enclaves in the Indonesian city of Surabaya. Its residents have been threatened with eviction by the city for many years because the village is in an area slated for tourism development. In an interview, Prayogo describes how the authorities employ “thugs” to terrorize those who refuse to abandon their houses. Half of the kampung has already moved out. But with no compensation and no place to go, Bo Hek resists.

Prayogo hadn’t planned to make this film about Bo Hek. As an activist, he has long advocated for the community’s land rights, and the two of them had become friends. One day, when Prayogo asked what he would do if he was forced out, in place of speaking, Bo Hek began to pray, and Prayogo began to film. Xiào 孝 is an act of witnessing, a moment of truth, of bare hope.

Excerpt below from Xiào 孝 by Cahyo Prayogo, courtesy of the artist.

Landscape Series #1: Unseen Contexts

A few years before making Landscape Series #1, Vietnamese artist Nguyễn Trinh Thi traveled across Vietnam, gathering stories related to history and memory. What most struck her about the landscapes she encountered was how dominant narratives were inscribed onto them: monuments, statues of leaders, war museums, cemeteries and memorials—all echoing an official version of the past. “Landscapes are witnesses to history whether you see it or not.” Nguyễn told me, “I was in the process of stepping back from these narratives that were being forced onto landscapes and thinking more deeply about empty spaces that suggest more than tell.”

Nguyễn searched the internet and newspapers for images of landscapes and came across many Vietnamese press photos that showed people pointing at specific locations. Until today, it is standard practice among journalists in Vietnam to ask local eyewitnesses, even bystanders, to point at a spot where something took place, and combine that photo with a caption to report an event. For Nguyễn, the staged nature of the press photographs is a metaphor for how history has been written in Vietnam: official history being theatricalized while personal stories and knowledge are neither expressed nor recorded.

By reappropriating this found footage in Landscape Series #1, the viewer becomes a second witness to an unseen, possibly traumatic past event. Perceiving the images retrospectively, from a distance and without context, the viewer is not privy to the specificities of injustice and violence. One doesn’t know that in fact, people are pointing to land they lost to corporations, or to the site where a nuclear plant will be built, or that one man is pointing to scars left by police torture. Instead, our imagination fills the gaps and we are immersed in the politically charged yet somehow poetic ambiguity of the untranslatable.

Excerpt below from Landscape Series #1 by Nguyễn Trinh Thi, courtesy of the artist.